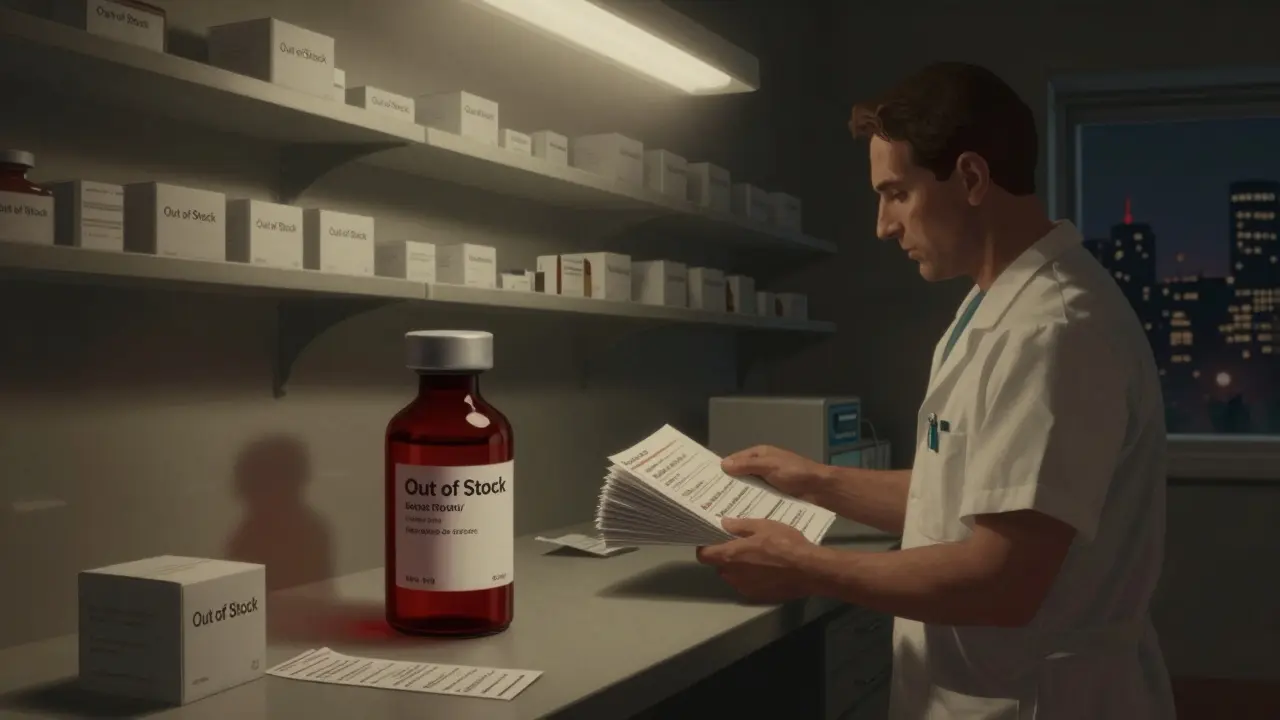

By the end of 2024, more than 300 drugs were in short supply across the U.S. - from life-saving antibiotics to chemotherapy agents. Hospitals were scrambling. Pharmacists were juggling five different brands of the same drug in a single week. Patients skipped doses because their medication simply wasn’t available. This isn’t a temporary glitch. It’s a broken system. And the federal government’s response in 2025-2026 is trying - and failing - to fix it.

The Scale of the Problem

Drug shortages aren’t rare. They’re routine. In 2024, the American Hospital Association recorded 323 active shortages. By September 2025, that number had dropped slightly to 277, but the FDA reported only 98 - a glaring mismatch. Why? Because different agencies count differently. Some track every drug with even a minor dip in supply. Others only count those that directly impact patient care. Either way, the result is the same: critical medicines are disappearing.

It’s not just about quantity. It’s about quality. Sterile injectables - things like saline, insulin, and cancer drugs - make up 73% of all shortages. Why? Because they’re cheap to make, hard to profit from, and easy to disrupt. Just three companies control nearly 70% of the U.S. market for these drugs. One factory shutdown, one quality control failure, and hospitals across the country are left without options.

The Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve (SAPIR)

In August 2025, President Trump signed Executive Order 14178, expanding the Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve - or SAPIR. This program doesn’t stockpile finished drugs. It stocks the raw ingredients - the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) - needed to make them.

The logic is simple: APIs are cheaper to store, last 3 to 5 years longer than pills or injections, and are easier to ship. The goal? To cut dependence on foreign suppliers, especially China, which provides about 80% of the APIs used in U.S. medications.

SAPIR targets 26 essential drugs: antibiotics, anesthetics, and some oncology medications. But here’s the problem - those 26 drugs account for less than 4% of all shortage incidents. The FDA’s own data shows that oncology drugs alone make up 31% of shortages, yet only a handful are included in the reserve. Critics call it a distraction. As Dr. Luciana Borio, former FDA Acting Chief Scientist, put it: "This is crisis response, not prevention."

What the Government Isn’t Fixing

While SAPIR grabs headlines, deeper problems go untouched.

First, there’s the economic issue. Making a generic injectable drug often costs more than it sells for. Companies don’t invest in backup factories or extra inventory because there’s no financial reward. The FDA can’t force a company to lose money.

Second, reporting is broken. Manufacturers are legally required to report potential shortages six months in advance. But in 2025, only 58% did. Small manufacturers - the ones most likely to fail - reported at a rate of just 18%. The FDA issued only 17 warning letters for non-compliance between 2020 and 2024. In the EU, under similar rules, they issued 142.

Third, funding is shrinking. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which once supported new manufacturing tech, saw its budget cut by 22% in 2026. State public health grants dropped $850 million. FEMA’s emergency response funding took a $1.2 billion hit. Meanwhile, the FDA approved 56 new manufacturing facilities in 2024 - but 42% of them were overseas.

The New Tools - And Why They’re Falling Short

In November 2025, the FDA launched its Enhanced Shortage Monitoring System. It uses AI to track 17 data streams: shipping delays, hospital purchase patterns, batch production records. It predicts shortages with 82% accuracy - 90 days in advance.

That’s impressive. But here’s the catch: hospitals still don’t know how to use it. The system is live, but only 28 states have fully integrated it into their emergency plans. Rural clinics lack the IT infrastructure. Pharmacists spend 10+ hours a week just managing shortages - and many still rely on phone calls and spreadsheets.

The HHS Draft Action Plan from September 2025 outlines four goals: Coordinate, Assess, Respond, Prevent. Sounds solid. But the Government Accountability Office found that only 35% of HHS’s own recommended actions have been implemented across agencies. The new Coordination Portal? Rated 2.1 out of 5 by healthcare workers. Usability is poor. Adoption is slow.

What’s Working - And What Could Work Better

There are bright spots. The FDA’s Early Notification Pilot Program, which requires manufacturers to report early, cut shortage durations by 28%. That’s the clearest success story we have. But the current administration has weakened that program’s enforcement.

Second-source manufacturing is another proven fix. When a drug has two or more manufacturers making it, shortages drop dramatically. The FDA’s new expedited review pathway for second-source applicants is promising. Fourteen applications are already in process - they could add redundancy for eight critical drugs by mid-2026.

And then there’s the EU. They require member states to stockpile essential medicines. They have a centralized monitoring system. Between 2022 and 2024, shortages fell by 37%. The U.S. could do the same. But instead of building a coordinated system, we’re building silos - SAPIR here, a reporting portal there, a patchwork of state-level programs.

The Human Cost

Behind every shortage number is a person.

Pharmacists are compounding chemotherapy drugs from raw chemicals because the finished product is gone. Nurses are checking blood pressure twice as often because they’ve switched a patient to a less effective substitute. Cancer patients are delaying treatment because their drug isn’t available. One in four Americans skipped doses due to unavailability - not because they couldn’t afford it, but because it didn’t exist.

Hospitals are spending an average of $1.2 million a year just managing shortages. That’s not profit. That’s survival. And it’s draining resources from patient care.

On Reddit, a pharmacist wrote: "I had to use five different manufacturers for the same drug in one week. Each had different dosing instructions. One had a different color. One smelled different. I was terrified I’d make a mistake."

Is There a Real Solution?

Yes - but it’s not what’s being sold.

Fixing drug shortages isn’t about stockpiling ingredients. It’s about fixing the market. We need to pay manufacturers fairly to make low-margin essential drugs. We need to reward them for having backup factories. We need to require transparency - not just report, but publish. We need to cut red tape so new U.S. facilities can open faster - 18 months in the EU, 30+ here.

And we need to stop pretending that 26 drugs are enough. When 98% of shortages involve drugs outside the reserve, we’re not solving the problem. We’re playing whack-a-mole.

The tools exist. The data is there. The AI can predict shortages before they happen. The EU has shown it can be done. But without changing the economic rules - without making it profitable to be prepared - we’ll keep seeing the same headlines: "Drug Shortage Hits Hospitals Again."

Why are drug shortages getting worse despite federal efforts?

Federal actions like the Strategic API Reserve focus on stockpiling raw ingredients, but they ignore the root causes: low profit margins on essential drugs, lack of manufacturing redundancy, and poor enforcement of reporting rules. Companies don’t invest in backup production because there’s no financial incentive. Meanwhile, only 58% of manufacturers report potential shortages, and enforcement is weak. Without fixing the economics of drug production, stockpiles won’t prevent the next crisis.

What drugs are most affected by shortages?

Sterile injectables make up 73% of all drug shortages. These include antibiotics like vancomycin, anesthetics like propofol, chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin, and common treatments like saline and insulin. Oncology drugs account for 31% of shortages, even though they’re only a small part of the federal reserve list. Generic drugs - especially those with thin profit margins - are most vulnerable because manufacturers have little reason to invest in extra capacity.

How does the FDA currently handle drug shortages?

The FDA works directly with manufacturers to resolve shortages by approving temporary imports, speeding up inspections, and offering regulatory flexibility. They maintain a public Drug Shortage Database tracking over 1,200 past and current shortages. Their new AI-powered monitoring system can predict shortages 90 days in advance with 82% accuracy. But enforcement is weak - only 17 warning letters were issued for non-reporting between 2020 and 2024, and compliance with reporting rules remains below 60%.

What’s the difference between SAPIR and traditional drug stockpiling?

Traditional stockpiling stores finished drugs - pills, vials, injections - which expire faster and are more expensive to store. SAPIR stores the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) - the raw chemicals used to make those drugs. APIs last 3 to 5 years longer, cost 40-60% less to stockpile, and are easier to transport. But SAPIR doesn’t guarantee a finished product will be made - it only ensures the ingredients are available if a manufacturer decides to produce.

Are U.S. drug shortages worse than in other countries?

Yes. The EU reduced shortages by 37% between 2022 and 2024 using mandatory stockpiling, centralized monitoring, and stronger enforcement. The U.S. has no national stockpile requirement, inconsistent reporting, and fragmented state-level responses. The FDA’s own data shows the U.S. has far more shortages per capita than peer nations. Regulatory delays also play a role - it takes 28-36 months to approve a new U.S. API facility, compared to 18-24 months in the EU.

What can hospitals do right now to manage shortages?

Hospitals are using alternative medications, increasing clinical monitoring, and training staff on substitution protocols. The FDA’s Early Notification Pilot Program has proven effective - hospitals using it saw 28% shorter shortage durations. But adoption is low. Pharmacist training is critical: 40 hours of training per pharmacist is recommended to safely manage substitutions. Community hospitals, with fewer resources, struggle the most. The best immediate step is joining the FDA’s shortage reporting network and using real-time data tools to anticipate disruptions.

What Comes Next?

The path forward isn’t about more stockpiles or more reports. It’s about incentives. Pay manufacturers to build backup capacity. Reward hospitals that maintain alternative supply chains. Penalize companies that hide supply risks. Fund domestic production - not just with grants, but with long-term contracts that guarantee demand.

Until then, the system will keep failing. And patients will keep paying the price.

Paul Barnes

January 18, 2026 AT 16:16The FDA’s AI system predicts shortages with 82% accuracy? That’s impressive-if you ignore the fact that no one’s using it. Hospitals still rely on spreadsheets and phone calls. The technology exists. The data is there. But the system is designed to look like it’s working, not actually fix anything. This isn’t innovation. It’s performance.

Manoj Kumar Billigunta

January 18, 2026 AT 21:08It’s heartbreaking to see how many people are affected by this. I’ve seen families delay treatment because a simple injection wasn’t available. No one should have to choose between their health and a broken supply chain. Real change means paying manufacturers fairly-not just stockpiling chemicals that may never become medicine.

Edith Brederode

January 18, 2026 AT 22:29This is so frustrating 😔 I work in a rural clinic and we’ve had to substitute chemo drugs three times this year. Each time, the dosing instructions are different. One batch smelled like chemicals. Another was a different color. I lost sleep wondering if I’d make a mistake. We need real backup systems-not just PR.

clifford hoang

January 19, 2026 AT 21:07Let’s be real: SAPIR is a distraction. The real agenda? Control. The government doesn’t want you to know that 80% of APIs come from China because they’re scared of the truth: they’ve outsourced our health to a regime that doesn’t care about us. This isn’t about medicine-it’s about power. The AI? A digital smoke screen. Wake up.

Arlene Mathison

January 20, 2026 AT 12:48Stop treating this like a tech problem. It’s an economic one. If making insulin or saline was profitable, companies would build ten factories overnight. We need long-term contracts, price guarantees, penalties for hiding shortages. No more bandaids. Time to pay people to do the right thing.

Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 20, 2026 AT 14:32My cousin just had to delay her cancer treatment because cisplatin was out. Again. She’s 29. She has a toddler. This isn’t policy debate-it’s life or death. And we’re arguing over whether to stockpile ingredients instead of making sure the medicine gets made. 🤦♀️

Greg Robertson

January 20, 2026 AT 14:37Hey, I get that SAPIR isn’t perfect-but at least it’s something. The EU has a centralized system, sure, but they also have universal healthcare. We don’t. Maybe instead of tearing it down, we should build on it? Start small. Expand the list. Reward transparency. Progress isn’t all or nothing.

Nadia Watson

January 21, 2026 AT 14:39It is imperative to recognize that the structural deficiencies in the pharmaceutical supply chain are not merely logistical, but deeply rooted in market disincentives. The absence of financial remuneration for redundancy, coupled with regulatory inertia, perpetuates systemic fragility. A coordinated, federally mandated stockpile of finished goods, aligned with international best practices, would be a more equitable solution than the current piecemeal approach.

Courtney Carra

January 22, 2026 AT 02:58Are we really surprised? We treat healthcare like a commodity, not a right. If you can’t profit from it, you don’t make it. That’s capitalism. But when your kid needs an antibiotic and there’s none left… that’s not capitalism. That’s moral failure. The AI doesn’t fix that. People do.

thomas wall

January 22, 2026 AT 13:32It is beyond contempt that the United States, the wealthiest nation on Earth, cannot guarantee access to basic life-saving medications. The EU manages it. Canada manages it. Even India, with its lower GDP, has better supply resilience. This is not incompetence. It is negligence. And those responsible must be held accountable.

Jacob Cathro

January 23, 2026 AT 21:37Bro the FDA approved 56 new facilities but 42% are overseas?? 😭 LMAO. We’re outsourcing our meds to China while calling it ‘national security.’ Meanwhile, pharmacists are mixing chemo from scratch like they’re in a Breaking Bad episode. This ain’t policy. It’s a dumpster fire with a PowerPoint.

sagar sanadi

January 25, 2026 AT 15:13Why does the government always pick the 26 most irrelevant drugs? Because they want you to think they’re doing something. Meanwhile, the real shortages-insulin, saline, antibiotics-are ignored. Classic. Let’s just stockpile the stuff no one uses and call it a win.

kumar kc

January 26, 2026 AT 00:27Fix the market. That’s it. No more excuses.

Art Gar

January 26, 2026 AT 06:25While the EU model presents a compelling comparative framework, its applicability to the United States is constrained by federalism, private-sector dominance, and divergent regulatory philosophies. A top-down national stockpile would require legislative overhauls and substantial fiscal commitments, neither of which are politically viable under current conditions. Incremental reform, though imperfect, remains the only feasible path forward.