Osteoporosis Risk Calculator

This calculator estimates your risk of osteoporosis based on medical factors related to secondary hypogonadism. Your results will help you understand potential bone health risks and guide conversations with your healthcare provider.

When hormones that control sexual function falter, the skeleton often pays the price. The link between secondary hypogonadism and osteoporosis is more than a coincidence-low sex hormones directly weaken bone, raising fracture risk for millions of men and women.

What Is Secondary Hypogonadism?

Secondary Hypogonadism is a condition where the testes or ovaries produce insufficient sex hormones because the pituitary or hypothalamus fail to signal properly. Unlike primary hypogonadism, the gonads themselves are structurally normal; the problem lies upstream in the brain’s hormonal cascade. Common triggers include pituitary tumors, chronic opioid use, severe weight loss, and systemic illnesses such as HIV or chronic kidney disease.

Understanding Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and micro‑architectural deterioration, leading to increased fragility and fracture risk. The disease is silent until a fracture occurs, often in the hip, spine, or wrist. While age‑related bone loss is universal, hormonal deficits can accelerate the process dramatically.

How Sex Hormones Keep Bones Strong

Both Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone that promotes bone formation by stimulating osteoblast activity and inhibiting osteoclast‑mediated resorption and Estrogen is a key regulator of bone remodeling that suppresses bone‑resorbing cells and maintains collagen quality play a protective role. In men, a portion of testosterone converts to estrogen via the aromatase enzyme, meaning both hormones contribute to bone health. When secondary hypogonadism reduces luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle‑stimulating hormone (FSH) release, downstream testosterone and estrogen levels drop, upsetting the delicate balance of bone remodeling.

Bone Mineral Density and the Hormonal Gap

Bone Mineral Density is a quantitative measure of the amount of mineral (mostly calcium and phosphorus) packed into a specific volume of bone, expressed in g/cm². Dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans track BMD over time. Studies show that men with untreated secondary hypogonadism lose BMD at a rate of 2-4% per year, comparable to post‑menopausal women. The loss is most pronounced at the lumbar spine and femoral neck-sites rich in trabecular bone, which is metabolically active and highly sensitive to hormonal changes.

Key Risk Factors and Who Is Most Vulnerable

- Age over 50: Natural decline in gonadal hormone output amplifies the effect of any upstream signal failure.

- Chronic glucocorticoid therapy: Steroids suppress GnRH release and directly accelerate bone resorption.

- Obesity or severe weight loss: Both extremes can disrupt hypothalamic signaling; bariatric surgery patients often develop secondary hypogonadism.

- Opioid dependence: Long‑term opioids blunt GnRH pulses, leading to low testosterone.

- Pituitary disorders: Tumors, surgery, or radiation damage the gland that drives LH/FSH production.

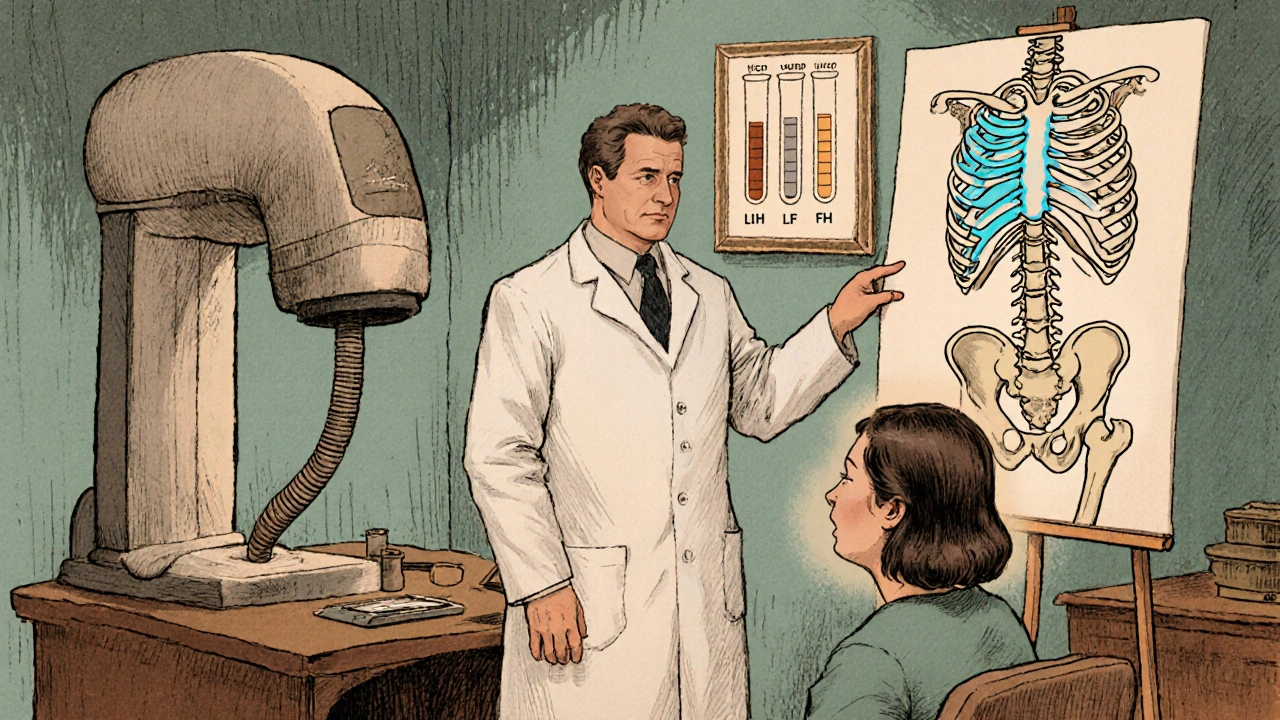

Diagnosing the Hormone‑Bone Connection

Clinical suspicion arises when a patient presents with low libido, fatigue, or muscle weakness alongside reduced BMD. The diagnostic work‑up includes:

- Serum total and free Testosterone levels (morning sample preferred).

- Estradiol measurement in men, especially if testosterone appears borderline.

- LH and FSH to differentiate primary from secondary hypogonadism.

- Prolactin and thyroid‑stimulating hormone (TSH) to rule out other pituitary disturbances.

- DXA scan for Bone Mineral Density assessment.

- Serum Vitamin D is a fat‑soluble vitamin essential for calcium absorption and bone mineralization and calcium levels to identify nutritional contributors.

Comparison of Bone Density Categories

| T‑Score | Classification | Fracture Risk | Typical Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ ‑1.0 | Normal | Low | Routine monitoring |

| ‑1.0 to ‑2.5 | Osteopenia | Moderate | Lifestyle changes, calcium/vitamin D |

| ≤ ‑2.5 | Osteoporosis | High | Pharmacotherapy + hormone replacement |

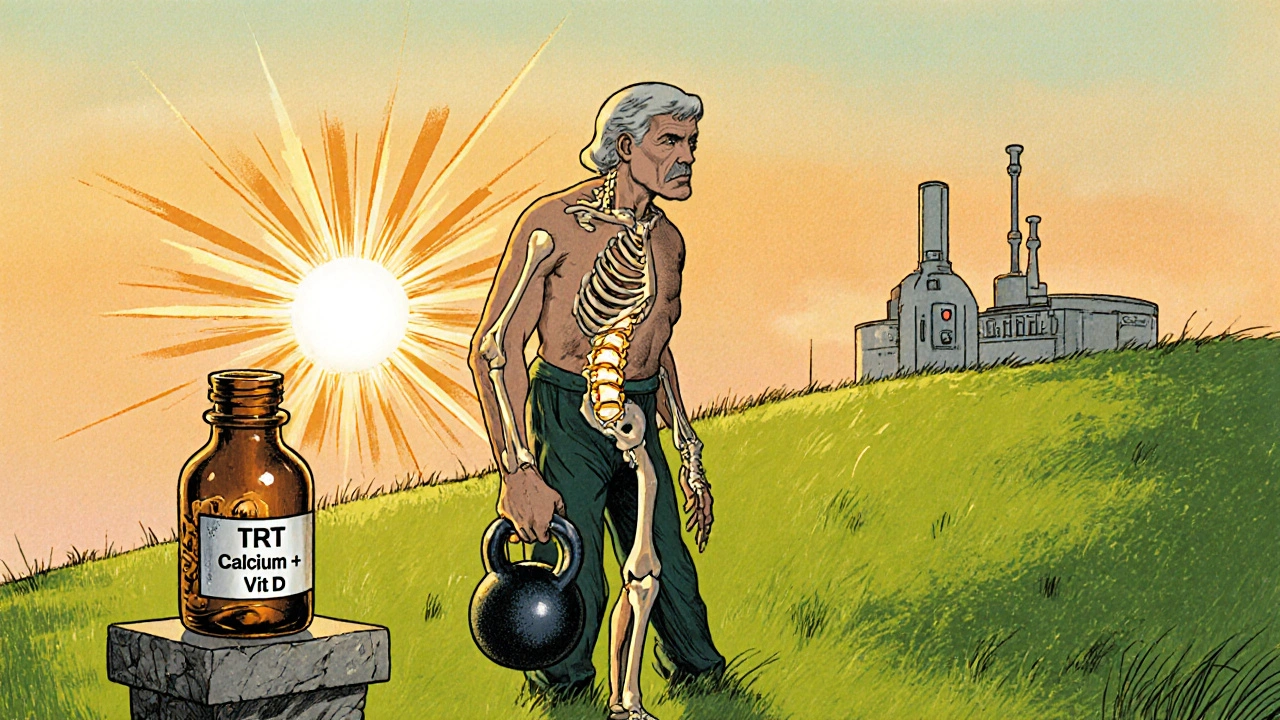

Treatment Options: Hormone Replacement and Beyond

Restoring sex hormones is the cornerstone of therapy when secondary hypogonadism is the primary driver of bone loss.

- Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT): Available as gels, patches, injections, or subcutaneous pellets. Goal is to maintain serum testosterone in the mid‑normal range (≈ 400-600 ng/dL). Studies report a 2-3% increase in lumbar spine BMD after 12 months of TRT.

- Gonadotropin Therapy: In select cases (e.g., men desiring fertility), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) mimics LH, stimulating endogenous testosterone production without suppressing spermatogenesis.

- Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs): For women with secondary hypogonadism, agents like raloxifene provide estrogen‑like bone protection without stimulating breast tissue.

- Bisphosphonates and Denosumab: Anti‑resorptive drugs are added when BMD loss persists despite hormonal correction.

Adjunctive measures round out the plan:

- Ensure adequate intake of Calcium is a mineral essential for bone formation, recommended at 1,000-1,200 mg/day for adults and vitamin D (800-1,000 IU/day).

- Weight‑bearing exercise (e.g., walking, resistance training) stimulates osteoblast activity.

- Avoid smoking and limit alcohol (< 2 drinks/day).

Monitoring and Long‑Term Outlook

After initiating therapy, repeat DXA scans at 12‑month intervals to gauge BMD response. Serum testosterone should be checked every 3-6 months until stable; thereafter, annual checks are sufficient. Patients with persistent low BMD despite optimal hormone levels may need referral to an endocrinologist for advanced bone‑targeted treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Secondary hypogonadism reduces testosterone and estrogen, which are vital for maintaining bone density.

- Low sex hormones accelerate loss of bone mineral density, especially in the spine and hip.

- Diagnosis combines hormone panels with DXA scanning and assessment of vitamin D and calcium status.

- Hormone replacement (TRT, hCG, SERMs) plus standard osteoporosis therapy can halt or reverse bone loss.

- Regular monitoring of BMD and hormone levels is essential for long‑term fracture prevention.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can men with secondary hypogonadism develop osteoporosis as quickly as post‑menopausal women?

Yes. When testosterone falls below 300 ng/dL, bone loss rates approach those seen in women after menopause, especially at trabecular sites like the lumbar spine.

Is testosterone therapy enough to stop bone loss?

For many patients, restoring normal testosterone levels stabilizes BMD and can even add a few percent over a year. However, if osteoporosis is already established, combining TRT with anti‑resorptive medication yields the best results.

What lifestyle changes help protect bone while treating hypogonadism?

Focus on calcium‑rich foods (dairy, leafy greens), vitamin D supplementation, regular weight‑bearing exercise, quitting smoking, and moderating alcohol intake.

Do women with secondary hypogonadism also face higher fracture risk?

Absolutely. Low estrogen from pituitary or hypothalamic failure accelerates bone turnover, making women susceptible to vertebral and hip fractures even before the typical post‑menopausal age.

How often should BMD be re‑checked after starting treatment?

A follow‑up DXA at 12 months is standard. If BMD improves, the next scan can be spaced to 2-3 years; if it plateaus or declines, more frequent monitoring is warranted.

Brian Van Horne

October 18, 2025 AT 15:22While the mechanistic link between secondary hypogonadism and bone demineralisation is well‑established, clinicians often overlook routine hormonal profiling in patients presenting with unexplained osteopenia.

Norman Adams

October 22, 2025 AT 02:42Oh, brilliant, another lecture on how hormones affect bones-because we all needed a reminder that the endocrine system isn’t just for mood swings.

Karla Johnson

October 25, 2025 AT 14:02It is striking how secondary hypogonadism, a disorder often rooted in hypothalamic or pituitary dysfunction, can precipitate a cascade of skeletal deterioration that mirrors, and in some cases exceeds, post‑menopausal bone loss. The reduction in luteinising hormone and follicle‑stimulating hormone leads to a downstream decline in both testosterone and estradiol, hormones that are pivotal for osteoblast activation and osteoclast inhibition. In men, the aromatisation of testosterone to estradiol supplies the majority of estrogenic activity necessary for maintaining trabecular micro‑architecture, especially in the lumbar spine. When this conversion is impaired, the balance tips toward resorption, resulting in measurable decreases in bone mineral density as early as six months after diagnosis. Studies employing dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry have consistently shown a 2‑4 % annual loss in BMD at the femoral neck and lumbar vertebrae among untreated patients. Moreover, chronic opioid use, a common iatrogenic cause, further suppresses gonadotropin release, compounding the osteoporotic risk. It is not merely the hormonal deficit that matters; associated factors such as reduced muscle mass, diminished physical activity, and altered calcium metabolism synergise to accelerate fragility. Vitamin D insufficiency, frequently observed in this cohort, hampers calcium absorption, thereby exacerbating the bone turnover imbalance. The clinical presentation often includes insidious back pain or reduced functional capacity, yet many patients remain asymptomatic until a low‑impact fracture occurs. Early recognition through a combination of serum testosterone, estradiol, LH, FSH, and DXA scanning can facilitate timely intervention. Testosterone replacement therapy, when titrated to physiological levels, has demonstrated modest yet significant gains in lumbar spine BMD, typically 2‑3 % over a year, and can also improve lean body mass and muscle strength, further protecting the skeleton. In women, selective estrogen receptor modulators provide a non‑fertility‑compromising alternative that still confers bone protection. Nonetheless, hormone therapy alone may be insufficient for patients with established osteoporosis; adjunctive anti‑resorptive agents such as bisphosphonates or denosumab are often indicated. Regular monitoring of hormone levels and repeat DXA at 12‑month intervals guide therapeutic adjustments and help prevent irreversible bone loss. In summary, the interplay between secondary hypogonadism and osteoporosis is a multifaceted process that demands a comprehensive, multidisciplinary management strategy to preserve skeletal health.

Ayla Stewart

October 27, 2025 AT 20:35I appreciate the thorough overview; for patients, the key takeaway is to ensure vitamin D and calcium are addressed alongside hormone therapy.

Poornima Ganesan

October 30, 2025 AT 18:02It’s astonishing how often primary care physicians miss the pituitary contribution to osteoporosis; a simple LH/FSH panel can differentiate secondary from primary causes without excessive testing.

Emma Williams

November 2, 2025 AT 01:35Good point. Simple labs do the trick.

Stephanie Zaragoza

November 4, 2025 AT 23:02Indeed, the literature unequivocally demonstrates that testosterone replacement, when administered to physiological levels, yields a statistically significant increase in lumbar spine BMD; however, clinicians must vigilantly monitor hematocrit, prostate‑specific antigen, and lipid profiles, lest adverse effects offset skeletal benefits.

Tracy O'Keeffe

November 7, 2025 AT 06:35Well, duh! If u’re gonna chase bone density numbers, ya might as well ditch the bland TRT protocols and hop onto the latest "bio‑hack" cocktail-think SARMs, selective estrogen modulators, and a dash of IGF‑1, all while chanting the ancient bone‑strength mantra.

Drew Waggoner

November 10, 2025 AT 04:02Optimising hormone levels is just one piece of the osteoporosis puzzle.

Joe Moore

November 13, 2025 AT 01:29Did you ever notice how the big pharma giants push bisphosphonates while keeping the real hormone cure on the down‑low? It’s like they’re scared of losing a profit stream.

James Mali

November 15, 2025 AT 09:02One could argue that the commodification of medical interventions reflects a broader societal tendency to prioritise short‑term gains over long‑term health, a pattern observable across many therapeutic domains.

Janet Morales

November 18, 2025 AT 06:29Honestly, if you think swapping a patch for a pill will magically fix fragile bones, you’re living in a fantasy world-real change comes from moving your butt off the couch and lifting weight, not just popping hormones.

Rajesh Singh

November 21, 2025 AT 03:55It is our ethical duty to educate patients that neglecting the endocrine–skeletal axis not only jeopardises their personal health but also burdens society with preventable fractures and the attendant suffering.