- 11

When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just have a patent. It has patent exclusivity and market exclusivity - two different kinds of legal shields that keep generics away. People often confuse them, but they’re not the same. One comes from the patent office. The other comes from the FDA. And understanding the difference can explain why some drugs stay expensive for years, even after patents expire.

Patent Exclusivity: The Legal Right to Block Copies

Patent exclusivity is what you get when you invent something new - a drug, a formula, a delivery method. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) gives you a 20-year monopoly from the day you file the patent application. That sounds like a long time, but here’s the catch: most drugs take 10 to 15 years just to get approved by the FDA. By the time the drug actually hits shelves, you’ve already used up half your patent life.

That’s why companies fight hard for Patent Term Extension (PTE). If the FDA took too long reviewing your application, you can ask for extra time - up to five years - but your total protected time after approval can’t go past 14 years. So if your drug got approved 12 years after you filed the patent, you might only get two years of actual market protection left.

Patents protect specific inventions. A composition-of-matter patent covers the actual molecule - that’s the strongest kind. But many companies file secondary patents too: for how the drug is made, how it’s packaged, or how it’s used to treat a new condition. These don’t always hold up in court, but they still delay generics. In fact, 68% of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book are secondary patents, not the core molecule.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Approval Lock

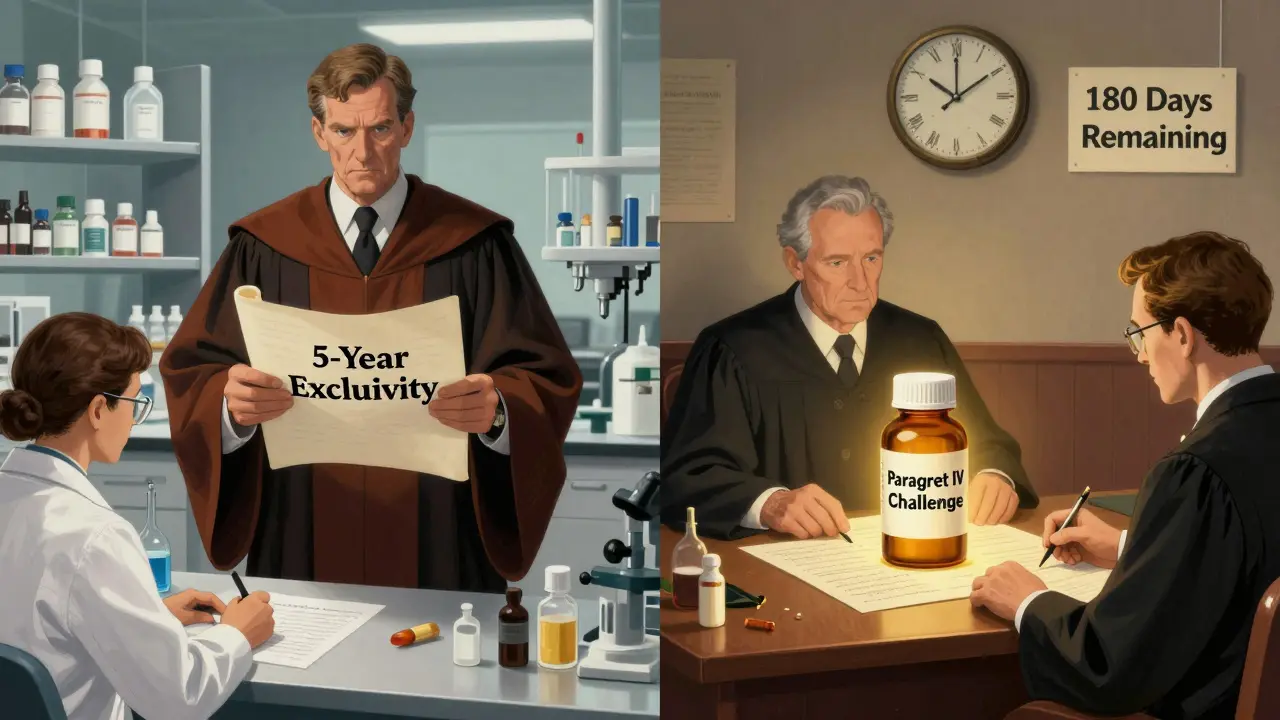

Market exclusivity has nothing to do with patents. It’s a reward from the FDA for doing the hard work of proving a drug is safe and effective. Once you get approval, the FDA won’t let anyone else copy your clinical data for a set number of years. That’s the real barrier to generics - not patents, but data.

For a brand-new chemical (called a New Chemical Entity or NCE), the FDA grants 5 years of exclusivity. During that time, no generic can even file an application using your data. After 5 years, they can submit an abbreviated application (ANDA), but they still have to wait for patents to expire.

There are other types too. Orphan drugs - those treating rare diseases - get 7 years. If you test your drug in kids, you get an extra 6 months. And for biologics - complex drugs made from living cells - you get 12 years. That’s longer than most patents last.

Here’s the kicker: you can have market exclusivity even if you don’t have a patent. Take colchicine. It’s been used since ancient Egypt. No one owned a patent on it. But in 2010, Mutual Pharmaceutical got FDA approval for a new formulation and received 10 years of exclusivity. The price jumped from 10 cents to nearly $5 per pill. No patent. Just exclusivity.

How They Work Together - Or Don’t

Think of patent exclusivity and market exclusivity like two keys. You need both to fully lock the door. But sometimes you only have one.

According to FDA data from 2021:

- 27.8% of branded drugs have both patent and market exclusivity

- 38.4% have patents but no market exclusivity

- 5.2% have market exclusivity but no patents

- 28.6% have neither

That means over 40% of drugs rely on patents alone. And more than 5% - that’s hundreds of drugs - are protected by exclusivity alone. In those cases, even if a generic manufacturer finds a way around the patent, the FDA still blocks them.

And here’s where it gets messy: the 180-day exclusivity for the first generic to challenge a patent. If a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification saying a patent is invalid or won’t be infringed, and they win, they get 180 days of exclusive rights to sell their version. That’s worth $100 million to $500 million in extra revenue. It’s a huge incentive - and a major reason why patent challenges are so common.

Why the Confusion Matters

Small biotech companies often think: “We have a patent, so no one can copy us.” But if they don’t apply for market exclusivity, the FDA can approve a generic as soon as the patent expires - even if that generic uses different manufacturing methods. That’s what happened with Trintellix, an antidepressant. Teva waited for the patent to expire, but the FDA still blocked them because of 3 years of regulatory exclusivity. They lost $320 million in delayed entry.

On the flip side, companies sometimes forget to claim exclusivity. Scendea Consulting found that between 2018 and 2022, 22% of innovators didn’t file for all available exclusivity periods. That’s an average of 1.3 years of free market protection thrown away per drug.

And it’s not just about money. It’s about access. When exclusivity lasts longer than the patent, patients pay more for longer. The Congressional Budget Office estimates pediatric exclusivity extensions have generated $15 billion in extra revenue since 1997 - not because the drug is better, but because the clock got reset.

What’s Changing Now?

The system is under pressure. The FDA launched its Exclusivity Dashboard in September 2023 - a public tool that shows every active exclusivity period in real time. Generic manufacturers are using it to plan their entries months ahead. That’s good for transparency, but bad for companies relying on secrecy.

The PREVAIL Act of 2023 proposes cutting biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. That’s a big deal. Biologics are the fastest-growing segment of the pharmaceutical market, and their exclusivity is often the only protection they have.

And globally, things are shifting too. The WTO’s waiver for COVID-19 vaccines opened the door to similar moves for other drugs. If countries start ignoring exclusivity rules, it could force the U.S. to rethink its entire model.

McKinsey predicts that by 2027, regulatory exclusivity will account for 52% of total market protection time - up from 41% in 2020. Patents are becoming easier to challenge. Exclusivity is becoming the real gatekeeper.

What This Means for Patients and Providers

When you see a drug price spike, don’t just blame the manufacturer. Look at the clock. Is it still under patent? Is it under exclusivity? Did someone just get a 6-month extension for pediatric studies? That’s what’s keeping the price high.

Doctors and pharmacists need to understand this too. A drug might have expired patents, but still be off-limits because of exclusivity. Patients asking for generics won’t get them - not because no one made one, but because the FDA won’t approve it yet.

And for anyone developing new drugs - whether you’re a big pharma company or a startup - you need a strategy. Don’t just file patents. File for exclusivity. Track both clocks. Miss one, and you lose millions.

The system was designed to balance innovation and access. But today, it’s tilted. Exclusivity is the new patent. And if you don’t know the difference, you’re playing the game blind.

Can a drug have market exclusivity without a patent?

Yes. Market exclusivity is granted by the FDA based on clinical data submitted for approval, not on patent status. For example, colchicine - an ancient drug with no active patents - received 10 years of exclusivity in 2010 after a new formulation was approved. The FDA blocked generics solely because of regulatory exclusivity, not patents.

How long does market exclusivity last for a new drug?

For a New Chemical Entity (NCE), the FDA grants 5 years of exclusivity. During this time, generic manufacturers cannot rely on the innovator’s clinical data to get approval. Other types include 7 years for orphan drugs, 12 years for biologics, and 6 months for pediatric studies. The clock starts on the day of FDA approval.

Do patents and exclusivity always expire at the same time?

No. Patents are filed early - often before clinical trials - and last 20 years from filing. Exclusivity starts at approval. So if a drug takes 12 years to get approved, its patent might have only 8 years left. But its exclusivity will still run for 5, 7, or 12 years from approval. They can overlap, run separately, or even end at different times.

Why do generic companies challenge patents?

Because the first generic to successfully challenge a listed patent gets 180 days of exclusive market rights - no other generic can enter during that time. This is worth $100 million to $500 million in extra revenue. It’s a huge incentive, even if the patent is weak. That’s why over 40% of new drugs face at least one Paragraph IV challenge.

Can the FDA approve a generic before the patent expires if exclusivity has ended?

No. Even if market exclusivity has expired, the FDA cannot approve a generic if any valid patent is still in force. The patent holder can file a lawsuit that triggers a 30-month stay on approval. Only when all patents expire - or are ruled invalid - can generics enter. Exclusivity and patents are independent, but both must be cleared.

What’s the difference between data exclusivity and market exclusivity?

Data exclusivity prevents other companies from using your clinical trial data to support their application. Market exclusivity prevents the FDA from approving any competing product at all. In the U.S., the 5-year NCE exclusivity includes both - you can’t use the data, and you can’t get approval. In the EU, they’re split: 8 years data exclusivity, then 2 years market exclusivity, plus 1 more year for new uses.

Amanda Eichstaedt

January 12, 2026 AT 23:39It’s wild how the system rewards paperwork more than actual innovation. You can invent a life-saving drug, but if you don’t file the right forms with the FDA, you’re left with nothing. And patients pay the price.

Jose Mecanico

January 14, 2026 AT 07:32Interesting breakdown. I never realized how much of the delay in generics comes from data exclusivity, not patents. Makes you wonder if the FDA’s role has become more of a gatekeeper than a protector.

Alex Fortwengler

January 15, 2026 AT 01:48Big Pharma’s got the whole system rigged. Patents? Pfft. They just file 20 stupid secondary ones just to stretch it out. And don’t get me started on biologics - 12 years? That’s corporate theft with a FDA stamp on it.

jordan shiyangeni

January 16, 2026 AT 18:30The fact that we allow a single corporation to monopolize access to a medication - even one derived from ancient herbal remedies - for a decade under the guise of ‘regulatory exclusivity’ is not just economically indefensible, it is morally bankrupt. This isn’t innovation; it’s rent-seeking dressed up as intellectual property. The FDA, in its current form, has become a regulatory arm of pharmaceutical lobbying, not a public health institution. And when you consider that pediatric exclusivity extensions have generated $15 billion in windfall profits since 1997 - none of which was tied to improved efficacy or safety - you begin to see that this entire framework was designed not to protect patients, but to enrich shareholders at the expense of public trust and fiscal sanity.

Abner San Diego

January 17, 2026 AT 09:44Why does America let these companies get away with this? In China or India, generics are cheap and everywhere. Here? You need a second mortgage just to fill a prescription. This isn’t healthcare - it’s corporate feudalism.

Eileen Reilly

January 18, 2026 AT 03:44so like… colchicine? 10 cents to $5? no cap. and the FDA just said ‘lol ok’? lmao. who’s signing off on this? 🤡

Monica Puglia

January 18, 2026 AT 04:30Thank you for explaining this so clearly. 🙏 It’s easy to blame drug companies, but the real issue is how the rules are stacked. I hope more doctors and pharmacists start talking about this with patients - it’s not just about cost, it’s about fairness.

Cecelia Alta

January 20, 2026 AT 01:15Okay but let’s be real - this whole system is a scam designed by lawyers and lobbyists. You’ve got some guy in a suit filing a patent for ‘a blue pill that’s round’ and suddenly it’s a 10-year monopoly. And then the FDA gives another 5 years because someone did a ‘pediatric study’ that literally just added a flavor. It’s not medicine - it’s a casino where the house always wins, and the players are people who can’t afford insulin. And don’t even get me started on how the first generic to challenge a patent gets 180 days of monopoly. That’s not competition - that’s a bribe to play dirty.

steve ker

January 20, 2026 AT 19:01George Bridges

January 21, 2026 AT 22:51I think what’s missing from this conversation is how much this affects rural communities. People aren’t just losing money - they’re skipping doses, splitting pills, or going without. The system wasn’t built for them. Transparency tools like the FDA’s dashboard are a start, but they won’t fix the root problem: profit over access.

Faith Wright

January 22, 2026 AT 13:13So let me get this straight - the government pays pharma companies to *not* let generics in? And we call this ‘incentivizing innovation’? 😂 Meanwhile, my cousin’s kid needs asthma meds and her mom works two jobs. This isn’t capitalism. It’s a joke with a white coat.