- 9

When you pick up a prescription for metformin or amoxicillin at your local pharmacy, you probably don’t think about how it got there. But behind that simple bottle is a complex, high-stakes system of wholesalers, pricing tiers, and profit margins that shape what you pay-and who makes money. This isn’t just about drugs. It’s about how the entire system of generic pharmaceutical distribution works, and why the cheapest drugs often generate the biggest profits for the middlemen.

The Three-Tier System No One Talks About

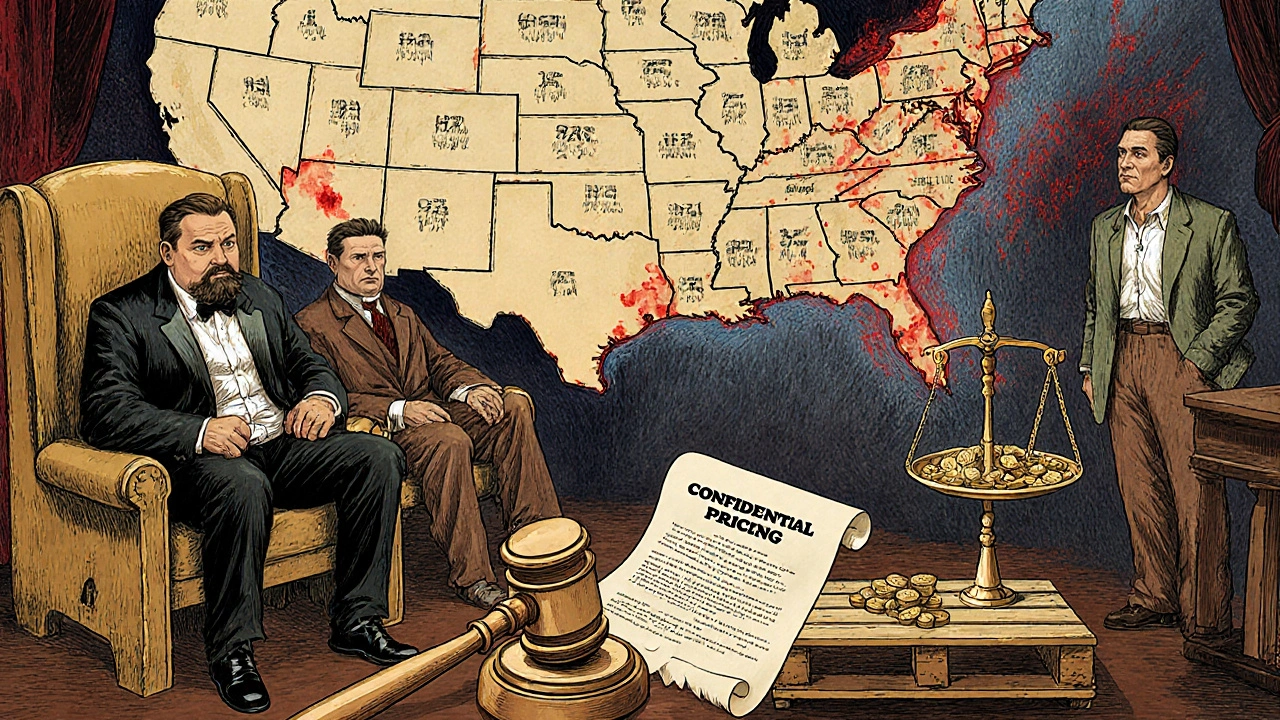

The path from a drug manufacturer to your medicine cabinet goes through three main players: manufacturers, wholesalers, and pharmacies. This structure was formalized in the U.S. after the Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987, but it’s still the backbone of how generic drugs move today. Manufacturers make the pills. Wholesalers buy them in bulk and store them. Pharmacies buy smaller amounts from wholesalers and sell them to patients. But here’s the twist: the biggest profits aren’t going to the companies making the drugs. They’re going to the distributors. The Big Three-AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson-control about 85% of the U.S. pharmaceutical wholesale market. That kind of concentration gives them serious power. They can negotiate lower prices from manufacturers, set their own markups, and even influence which drugs are available when.Why Generics Are the Secret Profit Engine

Generic drugs make up over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they only account for about 15-20% of total drug spending. That’s because they’re cheap. A 30-day supply of generic lisinopril might cost $4. But here’s where it gets strange: even though they’re low-priced, generics generate way more profit for wholesalers than brand-name drugs. In 2009, generics made up just 9% of wholesalers’ total revenue-but 56% of their gross profits. How? Because manufacturers of generics are forced to slash prices to win contracts with the Big Three. They compete on price, not branding. So wholesalers buy them at rock-bottom rates, then sell them at a markup that’s still low compared to branded drugs-but because they move so many units, the profits pile up. The numbers are stark. Wholesalers made eleven times more profit per unit on generic drugs than on brand-name drugs ($32 vs. $3). Pharmacies made nearly twelve times more. Meanwhile, manufacturers made about three times more on branded drugs than on generics ($58 vs. $18 per unit). The system is backwards: the people making the drugs earn less, while the people moving them earn more.How Pricing Actually Works (It’s Not What You Think)

Wholesalers don’t just add a flat 20% markup. Their pricing is layered and strategic. There are four main methods they use:- Cost-plus pricing: Add a fixed percentage to the cost of the drug and shipping. Simple, but ignores competition.

- Market-based pricing: Match what competitors charge. Keeps you in the game, but margins can shrink fast.

- Value-based pricing: Charge more if the drug is hard to get or in high demand. This is where shortages come in.

- Tiered pricing: The big one. Discounts kick in when you order more. Buy under 100 units? $10 per pill. Buy over 500? $7.50 each.

Why Generic Prices Go Up When They Should Go Down

You’d think more competition would mean lower prices. But that’s not always true. Between 2021 and 2022, generic drug prices fell as manufacturers flooded the market. But in 2023, things flipped. Drug shortages hit hard. When one company stops making a generic version of a common antibiotic, demand spikes for the remaining suppliers. Prices jump-even if the cost to make the drug hasn’t changed. This isn’t random. Wholesalers have a financial incentive to let shortages happen. When a drug is scarce, they can charge more. And because they control so much of the distribution, they can delay shipments to certain pharmacies, creating artificial scarcity. The Commonwealth Fund found that wholesalers play a direct role in shaping drug availability-not just by moving inventory, but by deciding who gets it and when.The Thin Margins That Keep the System Running

Despite the big profits on generics, wholesalers operate on razor-thin net margins-sometimes as low as 0.5%. That’s because they carry massive inventories. They need warehouses, trucks, staff, and software to track millions of pills. A single generic drug might have dozens of manufacturers and hundreds of buyers. Keeping everything balanced is a logistical nightmare. That’s why volume is everything. A wholesaler might make $0.10 profit on a single pill, but if they sell 10 million pills a month, that’s $1 million. They don’t need high margins per unit. They need massive scale. That’s why smaller distributors are disappearing. They can’t compete with the Big Three’s buying power, storage capacity, or delivery networks.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

Patients don’t directly pay wholesalers. But they pay for it anyway. When pharmacies pay more to wholesalers, they pass those costs on. Insurance companies negotiate discounts, but those savings don’t always reach patients with high deductibles or no coverage. Meanwhile, manufacturers of generics are squeezed. They’re stuck between falling prices and rising compliance costs. The real winners? The Big Three wholesalers. They’ve turned generic drugs into a volume-based cash machine. They don’t need to innovate. They don’t need to market. They just need to control the pipeline.What Could Change?

There’s growing pressure to fix this system. The USC Schaeffer Center has called for more competition and transparency. The Commonwealth Fund says regulators need to盯紧 wholesalers’ role in pricing and shortages. Some states are exploring direct manufacturer-to-pharmacy distribution to cut out the middleman. Others are pushing for public wholesale databases so prices aren’t hidden behind contracts. But change is slow. The system works-just not for everyone. Until there’s real pressure on the Big Three to open their books, generic drug pricing will keep being a game of numbers, not health.Why are generic drugs cheaper to buy but more profitable for wholesalers?

Generic drugs are cheaper because manufacturers compete on price to win bulk contracts. Wholesalers buy them at rock-bottom rates, then sell them at a small but consistent markup across massive volumes. Even a $0.10 profit per pill adds up to millions when you’re moving billions of units. Their profit isn’t in the price-it’s in the scale.

Do wholesalers cause drug shortages?

They don’t cause shortages directly, but they can worsen them. When a manufacturer stops making a drug, wholesalers may prioritize shipments to large hospitals or insurers that pay more. Smaller pharmacies get left waiting. Some wholesalers even delay restocking to keep prices high. This behavior is legal but controversial, and it’s been documented by the Commonwealth Fund and Drug Channels Institute.

Why don’t pharmacies just buy directly from manufacturers?

It’s not practical. Manufacturers sell in truckload quantities-thousands or millions of units. Most pharmacies need a few hundred pills a week. Wholesalers break down those bulk shipments into manageable sizes. They also handle logistics, returns, recalls, and regulatory paperwork. For small pharmacies, the cost and complexity of direct buying would be higher than using a wholesaler.

How do tiered pricing discounts work in practice?

If a wholesaler sells a generic drug at $10 per unit for orders under 100, they might drop the price to $8 for orders over 100 and $7 for orders over 500. This encourages pharmacies and clinics to order more at once, reducing the wholesaler’s shipping and handling costs per unit. The wholesaler still makes profit, but they save on operations and lock in long-term customers.

Is there a way to know what wholesalers are charging pharmacies?

Not easily. Wholesaler pricing is often hidden behind confidential contracts. Some states are starting to require price transparency, and a few online tools show average wholesale prices (AWP), but AWP is outdated and inflated. The real price-the Actual Acquisition Cost (AAC)-is what pharmacies pay, and it’s rarely public. That lack of transparency is one of the biggest complaints in the industry.

Darragh McNulty

November 21, 2025 AT 08:47Willie Doherty

November 21, 2025 AT 23:56David Cusack

November 23, 2025 AT 14:41Elaina Cronin

November 23, 2025 AT 15:08Paula Jane Butterfield

November 24, 2025 AT 11:55Simone Wood

November 26, 2025 AT 09:22Debanjan Banerjee

November 27, 2025 AT 21:41Steve Harris

November 29, 2025 AT 20:43Sandi Moon

November 30, 2025 AT 15:23