When you need dialysis, your body doesn’t just need a machine-it needs a reliable doorway into your bloodstream. That doorway is called dialysis access. And not all access types are created equal. The choice between a fistula, graft, or catheter isn’t just a medical decision-it affects how long you live, how often you end up in the hospital, and how much you can do every day.

Why Dialysis Access Matters More Than You Think

Hemodialysis pulls blood out of your body, cleans it, and puts it back. To do that safely and efficiently, you need a strong, stable connection to your blood vessels. Without it, treatments are slow, risky, or impossible. The three main types of access-fistulas, grafts, and catheters-each have their own strengths, weaknesses, and lifespans. But one stands above the rest: the arteriovenous (AV) fistula. According to the National Kidney Foundation, fistulas are the gold standard. They’re made by surgically connecting an artery directly to a vein, usually in your forearm. This lets your vein grow stronger over time, thickening its walls so it can handle repeated needle sticks during dialysis. A well-maintained fistula can last for decades. And here’s the kicker: patients using fistulas have a 36% lower risk of dying from dialysis-related complications than those using grafts, and more than 50% lower risk than those relying on catheters.AV Fistula: The Long-Term Winner

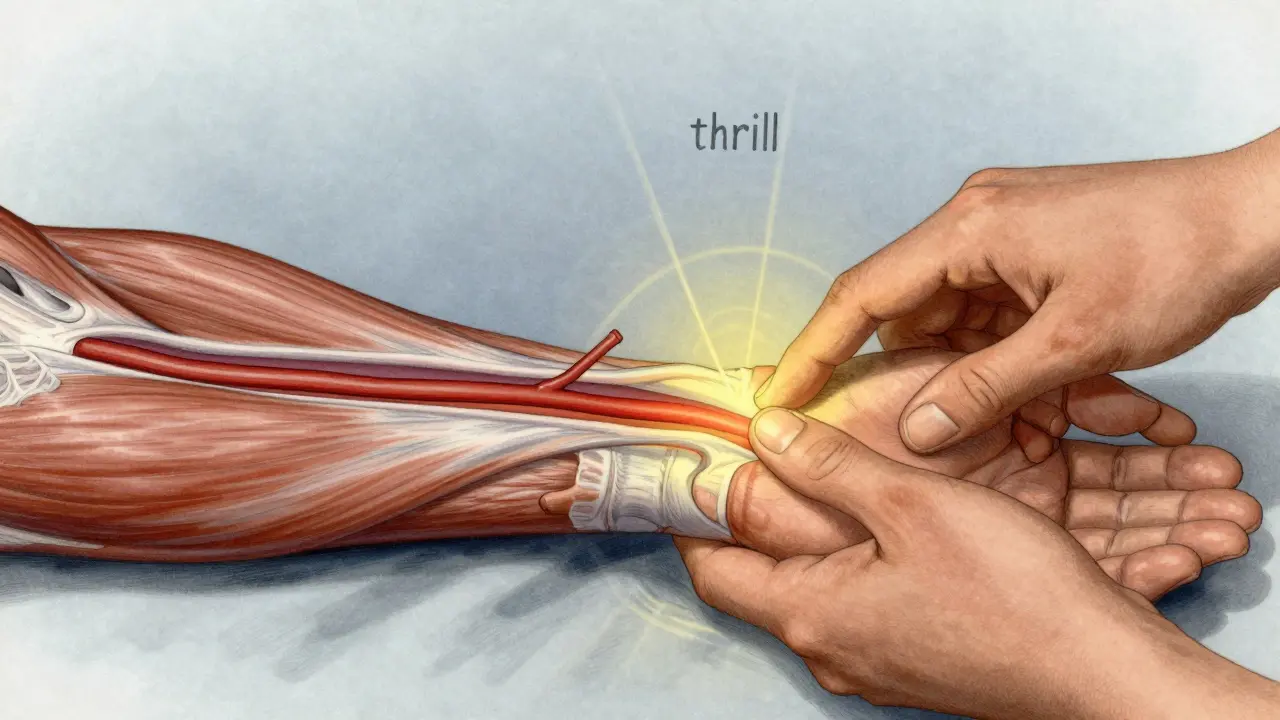

Fistulas are the most durable and safest option. They rarely get infected, clot less often, and don’t require synthetic materials. But they’re not instant. It takes 6 to 8 weeks for the vein to mature enough to use. That’s why many patients start with a catheter while waiting. Once mature, a fistula feels like a low hum under your skin-a vibration called a “thrill.” You can check it daily by gently pressing your fingers over the access site. If the thrill disappears or feels weak, call your care team. That’s often the first sign of a clot forming. Daily care is simple: keep it clean, avoid tight clothing or sleeping on that arm, and never let anyone take your blood pressure or draw blood from that arm. Most patients learn to check their thrill in just a few training sessions. Studies show that people who get educated about fistula care before starting dialysis have 25% fewer complications in their first year. The downside? Not everyone qualifies. If your veins are too small or damaged from diabetes or high blood pressure, your surgeon might not be able to create a fistula. That’s where vein mapping comes in-a painless ultrasound test done before surgery to see which vessels are strong enough. If your veins aren’t up to it, the next best option is a graft.AV Graft: The Middle Ground

An AV graft is a synthetic tube-usually made of a material called PTFE-that connects an artery to a vein. It’s used when your own veins aren’t strong enough for a fistula. The good news? It’s ready to use in just 2 to 3 weeks, much faster than a fistula. But grafts come with trade-offs. They’re more prone to clotting and infection than fistulas. About 30 to 50% of grafts need at least one procedure in the first year to keep them open. These interventions can include balloon angioplasty or stent placement, which are minimally invasive but still add risk and cost. Patients with grafts often need monthly check-ups to monitor blood flow. Unlike fistulas, grafts don’t have a natural “thrill”-instead, your care team uses a Doppler ultrasound to check flow rates. If the flow drops below a certain level, it’s a warning sign. Left unchecked, clots can form and block the graft completely, requiring emergency removal or replacement. Grafts typically last 2 to 3 years before needing replacement. While they’re not ideal, they’re a solid backup plan. And for patients who can’t get a fistula, they’re often the best path forward.

Catheters: Temporary, But Sometimes Permanent

Central venous catheters are soft tubes inserted into large veins in your neck, chest, or groin. They work immediately, which is why they’re used for emergency dialysis or while waiting for a fistula or graft to heal. But here’s the truth: catheters are the riskiest option. They’re the leading cause of bloodstream infections in dialysis patients. Studies show catheter use leads to 2.1 times more fatal infections than fistulas. Every time you shower or bathe, you have to protect the catheter site with waterproof dressing. Even then, bacteria can sneak in. The numbers are stark. For every 1,000 catheter days, there are 0.6 to 1.0 bloodstream infections. That adds up fast. Over a year, a patient on a catheter is far more likely to be hospitalized than someone with a fistula. And the cost? The U.S. healthcare system spends an extra $1.1 billion annually treating complications from catheters that could have been avoided with better access planning. Some patients end up on catheters permanently because they can’t get a fistula or graft. But that’s not because it’s the best choice-it’s because the system failed them. Black patients, for example, are 30% less likely to get fistulas than white patients, even when their medical needs are identical. That’s a gap that needs fixing.What You Can Do to Protect Your Access

No matter what type of access you have, your daily actions make a difference.- For fistulas: Check your thrill every day. Wash the area with soap and water before each dialysis session. Avoid pressure on the arm. Never let anyone use that arm for blood pressure or IVs.

- For grafts: Watch for swelling, redness, or warmth. Report any changes immediately. Attend all scheduled flow checks.

- For catheters: Follow sterile dressing change protocols exactly. Never touch the catheter ends. Keep the site dry at all times. If you notice fever, chills, or redness around the exit site, go to the ER.

New Tech, Better Outcomes

The field is changing. In 2022, the FDA approved the first wireless sensor for dialysis fistulas-Manan Medical’s Vasc-Alert. It monitors blood flow in real time and sends alerts if a clot is forming. In trials, it cut thrombosis events by 20%. Researchers are also testing pre-dialysis exercise programs. Just 30 minutes of arm exercises a day-like squeezing a stress ball or doing wrist curls-can improve fistula maturation rates by 15 to 20%. It’s simple, cheap, and effective. And on the horizon: bioengineered blood vessels. Humacyte’s human acellular vessel is in late-stage trials. It’s a lab-grown tube that your body can accept without rejection, perfect for patients with no usable veins. If it gets approved, it could change the game for thousands.The Bottom Line

Your dialysis access isn’t just a medical device-it’s your lifeline. Fistulas are the best. Grafts are the backup. Catheters are the last resort. And the longer you wait to plan, the more likely you are to end up with a catheter by default. Talk to your nephrologist early. Ask about vein mapping. Push for a fistula if you’re eligible. If you can’t get one, understand why. And if you’re on a catheter, know the signs of infection and don’t wait to act. The data doesn’t lie. Better access means longer life, fewer hospital stays, and more freedom. You deserve that. And with the right care, you can have it.What is the best type of dialysis access?

The best type is an arteriovenous (AV) fistula. It’s made from your own blood vessels, has the lowest risk of infection and clotting, and can last for decades. Clinical guidelines from the National Kidney Foundation and KDOQI recommend it as the first choice for all dialysis patients who are eligible.

How long does it take for a fistula to be ready for dialysis?

It usually takes 6 to 8 weeks for a fistula to mature. During this time, the vein grows larger and stronger from the increased blood flow. You can’t use it for dialysis until it’s fully matured. If you need dialysis before then, a temporary catheter is used.

Can I shower with a dialysis catheter?

Yes, but only with strict precautions. You must cover the catheter site with a waterproof dressing designed for dialysis access. Never let water touch the catheter or its exit site. Even a small amount of moisture can introduce bacteria and cause a life-threatening infection. Many patients use specialized shower bags or plastic wrap secured with tape.

Why do some patients end up with catheters instead of fistulas?

Many patients have small, weak, or damaged veins due to diabetes, high blood pressure, or prior surgeries. In these cases, a fistula can’t be created. Others may not get referred for vein mapping early enough, or face delays in surgery. Studies also show racial disparities-Black patients are 30% less likely to receive fistulas than white patients, even when medically eligible.

How often do grafts need to be fixed?

About 30 to 50% of AV grafts require at least one intervention within the first year. These procedures-like balloon angioplasty or stent placement-are done to open clots or narrow areas. Grafts are more prone to clotting than fistulas because they’re made of synthetic material, which your body can react to over time.

What are the signs my dialysis access is failing?

For a fistula: loss of the normal vibration (thrill), swelling, pain, or coldness in the arm. For a graft: loss of blood flow detected during monitoring, swelling, or discoloration. For a catheter: fever, chills, redness, pus, or pain around the exit site. Any of these signs mean you need to contact your care team immediately-don’t wait.

Can I exercise with a dialysis fistula?

Yes, but avoid heavy lifting or direct pressure on the access arm. Light exercises like squeezing a soft ball or wrist curls can actually help the fistula mature faster. Studies show pre-dialysis arm exercises can improve maturation rates by 15 to 20%. Always check with your care team before starting any new routine.

How can I reduce my risk of infection with a catheter?

Follow your nurse’s instructions exactly. Wash your hands before touching the catheter. Use sterile gloves and antiseptic when changing dressings. Never let the catheter ends touch anything dirty. Avoid swimming or soaking in bathtubs. If you notice fever, redness, or discharge, go to the emergency room right away-catheter infections can turn deadly fast.

Brian Furnell

December 21, 2025 AT 14:10AV fistula is the gold standard, no doubt-36% lower mortality vs. grafts, >50% vs. catheters. But let’s not gloss over the maturation timeline: 6–8 weeks is an eternity when you’re in uremic distress. The real issue isn’t clinical superiority-it’s systemic delay. Vein mapping should be mandatory at CKD Stage 4, not Stage 5. Why are we still playing whack-a-mole with catheters? We’ve had the data since 2010. Why is this still a crisis?

Siobhan K.

December 22, 2025 AT 09:52Let’s be real-fistulas aren’t magic. They’re just the least-bad option. I’ve seen patients with perfect veins who still get grafts because the surgeon’s schedule is full and the insurance won’t cover pre-op mapping. The system doesn’t care if you live or die-it cares if the billing code gets submitted on time. And don’t even get me started on the ‘catheter is temporary’ lie. For many, it’s permanent because no one had the foresight to act early.

Orlando Marquez Jr

December 24, 2025 AT 07:03It is imperative to underscore the clinical imperative of arteriovenous fistula utilization as the primary vascular access modality for hemodialysis patients, per KDOQI guidelines and evidence-based protocols from the National Kidney Foundation. The statistical disparity in mortality outcomes between fistula, graft, and catheter modalities is both statistically significant and clinically profound, with p-values < 0.001 across multiple prospective cohort studies. Furthermore, the economic burden of catheter-related bloodstream infections, estimated at $1.1 billion annually in the United States, constitutes a preventable fiscal externality that demands policy intervention.

Stacey Smith

December 24, 2025 AT 12:17Stop making excuses. If you’re on dialysis, you get a fistula. Period. No ifs, ands, or buts. If your veins are bad, tough. That’s why we have grafts. Catheters? That’s not a medical choice-that’s a personal failure. You didn’t plan. You didn’t care. Now you’re a liability to the system. Get it together.

Ben Warren

December 26, 2025 AT 08:19It is a well-documented, empirically validated fact that the use of central venous catheters as a primary access modality for hemodialysis constitutes a profound systemic failure of both clinical governance and patient advocacy. The 2.1-fold increase in fatal sepsis rates compared to fistula usage is not an accident-it is the direct consequence of fragmented care, under-resourced nephrology practices, and institutionalized neglect of patient autonomy in favor of procedural expediency. Furthermore, the racial disparity in fistula placement-30% lower for Black patients despite equivalent clinical eligibility-is not merely a statistical anomaly; it is a manifestation of structural racism embedded within the U.S. healthcare delivery infrastructure. The persistence of this inequity, despite 15 years of published guidelines, constitutes a moral failure on a national scale.

Sandy Crux

December 27, 2025 AT 22:59Interesting how everyone treats fistulas like some kind of holy grail… but have you considered that maybe the body’s natural vessels aren’t always the best? Synthetic grafts have been engineered for durability, consistency, and predictability. And catheters? They’re not ‘last resort’-they’re ‘adaptive.’ The body adapts. Why can’t medicine? Also, who says ‘thrill’ is even reliable? I’ve had mine for 7 years and it’s never vibrated once. Yet my flow rates are perfect. Maybe we’re romanticizing biology because it’s easier than admitting we don’t fully understand vascular physiology.

Hannah Taylor

December 29, 2025 AT 20:43wait so the gov is hiding the truth? they dont want us to know that catheters are actually safer because they can be removed if the dialysis machine is hacked?? i read this on a forum and now im scared to touch my fistula. also why do all the doctors wear white coats? are they hiding something??

Jason Silva

December 31, 2025 AT 03:38Bro, fistulas are LIFE. 🙌 I’ve had mine for 5 years, no infections, no hospital trips. Check your thrill every day like your life depends on it-because it does. 💪 And yeah, catheters? Total nightmare. My cousin got sepsis from one. Don’t be that guy. Exercise your arm. Squeeze a ball. Be proactive. You got this! ❤️🩸

mukesh matav

January 1, 2026 AT 14:48Thank you for this clear explanation. In India, many patients start with catheters because access to specialists is limited. We need more awareness, not just in the U.S. But your point about vein mapping is important. Even here, if we can do simple ultrasound checks early, more people could avoid catheters. Small steps matter.

Peggy Adams

January 3, 2026 AT 14:39why is everyone so obsessed with fistulas? i mean, i got my catheter and i’m fine. why do i need to check some ‘thrill’? sounds like a scam to sell more ultrasounds. also, who says i can’t just use a catheter forever? i don’t care about ‘gold standards.’ i care about not getting cut open again.

Sarah Williams

January 5, 2026 AT 02:38This is the kind of info every new dialysis patient needs. Seriously-share this. I wish I’d known all this before my first session. Fistula care saved my life. Don’t wait until you’re in crisis to learn. Talk to your nurse. Ask questions. You’re not alone.

Theo Newbold

January 5, 2026 AT 03:59The Vasc-Alert sensor? A band-aid on a hemorrhage. Real progress would be mandatory pre-dialysis vascular assessment at Stage 3 CKD-not Stage 5. The fact that we’re celebrating a $2,000 sensor instead of systemic reform proves how broken this system is. And pre-dialysis arm exercises? Cute. But if your vein is obliterated by diabetes and hypertension, a stress ball won’t fix structural vascular collapse. This is triage medicine dressed up as innovation.