Dementia Risk Factor Checker After TIA

This tool helps you understand how your current health factors affect dementia risk after a TIA. Based on evidence from clinical studies, it calculates a relative risk score using modifiable factors discussed in the article.

What is a Transient Ischemic Attack?

A brief, reversible episode of neurological dysfunction caused by a temporary blockage of blood flow to the brain. It typically lasts a few minutes and resolves completely, which is why it’s often called a “mini‑stroke.” Common symptoms include sudden weakness or numbness on one side of the body, trouble speaking, vision changes, or loss of balance. Although symptoms disappear, a TIA signals that the brain’s blood vessels are already compromised.

How a TIA Highlights Brain Vulnerability

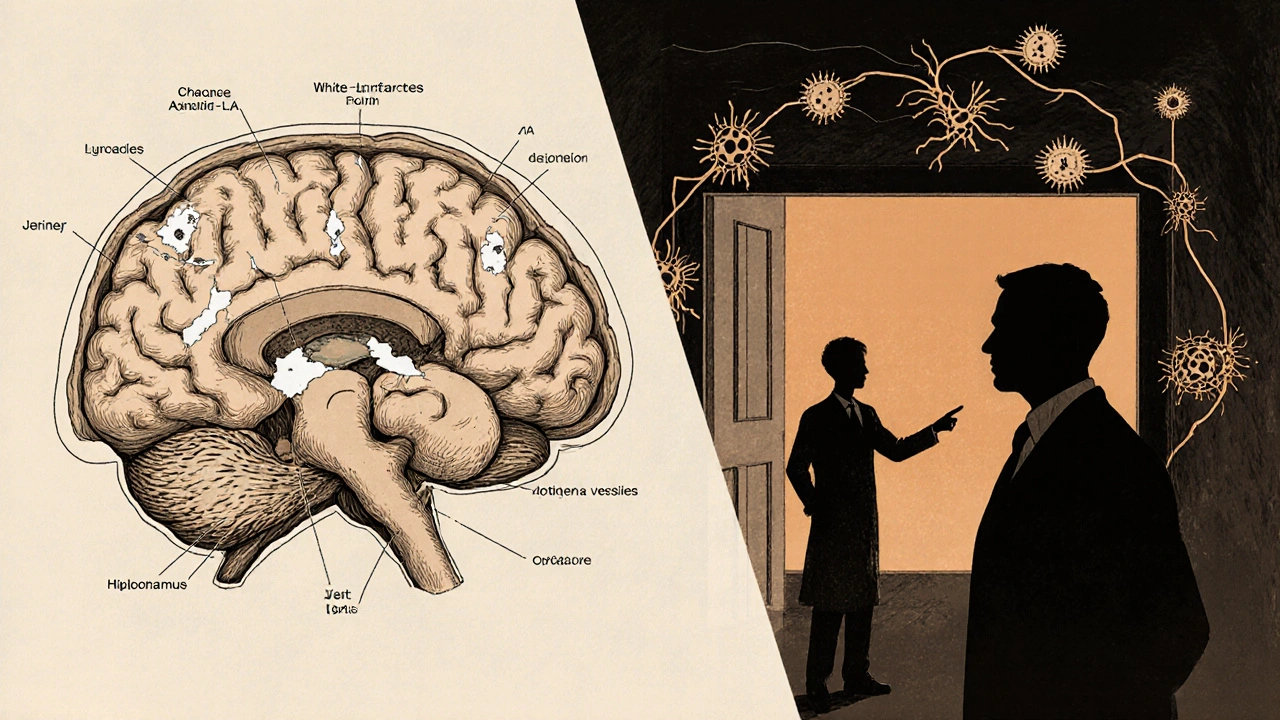

When a TIA occurs, the same vessels that caused the brief interruption are likely to develop plaque, narrowing, or clot formation over time. This chronic damage creates a fertile ground for silent infarcts-small areas of dead brain tissue that never produce obvious symptoms but accumulate silently. Studies using neuroimaging have shown that up to 30% of people with a recent TIA already have unnoticed white‑matter lesions.

Understanding Dementia and Its Main Types

Dementia is a clinical syndrome marked by progressive loss of memory, reasoning, language, and everyday functioning. The two most common forms are Alzheimer’s disease, driven primarily by amyloid plaques and tau tangles, and vascular dementia, which results from repeated vascular insults such as strokes or TIA‑related microinfarcts. While Alzheimer’s accounts for roughly 60‑70% of cases, vascular contributions are increasingly recognized as a modifiable risk factor.

Evidence Linking TIA to Higher Dementia Risk

Large‑scale cohort studies from the United States, Europe, and Asia have consistently reported a higher incidence of dementia after a TIA. For example, the Rotterdam Scan Study followed 2,500 participants aged 55+ for an average of 8 years; those who experienced a TIA had a 1.9‑fold increased risk of developing any form of dementia compared with those without a TIA. A 2023 meta‑analysis of ten prospective studies (total n≈150,000) found a pooled relative risk of 1.68 (95% CI 1.45‑1.95) for all‑cause dementia after a TIA.

| Study | Follow‑up (years) | TIA group (%) | Control group (%) | Relative Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotterdam Scan Study | 8 | 12.4 | 6.6 | 1.88 |

| Framingham Heart Study | 10 | 9.2 | 5.1 | 1.80 |

| Chinese Cohort 2022 | 5 | 7.5 | 3.9 | 1.92 |

Why Does a TIA Raise Dementia Risk? Biological Pathways

Three main mechanisms connect a TIA to later cognitive decline:

- Vascular injury: Even a brief ischemic episode can damage the endothelial lining of cerebral vessels, promoting chronic inflammation and micro‑bleeds. Over time, these lesions disrupt the brain’s white‑matter integrity, a key predictor of executive dysfunction.

- Silent infarcts: Neuroimaging shows that many TIA survivors accumulate subclinical infarcts within the hippocampus and frontal lobes-areas critical for memory and planning. Each silent infarct adds roughly a 5‑10% increase in dementia odds.

- Interaction with Alzheimer pathology: Vascular compromise can impair the clearance of amyloid‑beta, accelerating plaque buildup. Studies using PET scans have observed higher amyloid burden in TIA patients who later develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Spotting Early Cognitive Changes After a TIA

Because the first signs are often subtle, clinicians recommend routine cognitive screening at 3‑month, 12‑month, and yearly intervals following a TIA. Tools such as the Mini‑Mental State Examination (MMSE) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) can detect mild deficits before they interfere with daily life. Red flags include difficulty finding words, frequent forgetfulness, slowed decision‑making, and trouble multitasking.

Prevention Strategies to Lower Dementia Risk After a TIA

Once a TIA has occurred, aggressive risk‑factor management becomes crucial. The following evidence‑based measures have the strongest impact:

- Antiplatelet therapy: Daily low‑dose aspirin or clopidogrel reduces recurrent ischemic events by 20‑30% and indirectly lowers dementia incidence.

- Blood pressure control: Targeting < 130/80 mmHg (especially in patients with hypertension) cuts both stroke and vascular dementia risk.

- Statin use: Statins improve endothelial function and have been linked to a modest 10% reduction in cognitive decline.

- Atrial fibrillation management: Anticoagulation with warfarin or direct oral anticoagulants prevents cardio‑embolic TIAs, a major source of cerebral micro‑infarcts.

- Lifestyle modifications: Regular aerobic exercise, Mediterranean‑style diet, smoking cessation, and limiting alcohol intake support vascular health and neuroplasticity.

Regular follow‑up with a neurologist or stroke specialist ensures medication adherence, monitors for new symptoms, and updates imaging when needed.

Practical Checklist for Patients and Caregivers

- Schedule a comprehensive cognitive assessment within 3 months of the TIA.

- Ask your doctor about starting or continuing antiplatelet therapy.

- Track blood pressure daily; aim for the target range set by your clinician.

- Review all current medications for potential interactions that might affect cognition.

- Incorporate at least 150 minutes of moderate‑intensity exercise each week.

- Adopt a diet rich in leafy greens, fish, nuts, olive oil, and berries.

- Keep a symptom diary-note any new memory lapses, language trouble, or balance issues.

- Plan annual brain imaging (MRI or CT) if recommended, to catch silent infarcts early.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does every TIA lead to dementia?

No. While a TIA raises the probability of later cognitive decline, many people never develop dementia, especially if they control vascular risk factors aggressively.

How soon after a TIA should I be screened for cognitive problems?

Guidelines suggest an initial assessment at 3 months, followed by another at 12 months and then yearly if results are normal.

Can medication alone prevent dementia after a TIA?

Medication (antiplatelets, statins, antihypertensives) is a key part of prevention, but lifestyle changes and regular cognitive monitoring are equally important.

Is vascular dementia the only type linked to TIA?

TIA primarily contributes to vascular dementia, but its impact on cerebral blood flow can also accelerate Alzheimer’s pathology, making mixed‑type dementia common.

What imaging modality best detects silent brain injury after a TIA?

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with diffusion‑weighted and fluid‑attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences is the gold standard for spotting micro‑infarcts and white‑matter changes.

Ritik Chaurasia

October 22, 2025 AT 15:08In many parts of India the silent burden of TIA is often ignored until a full‑blown stroke hits. Our public health system still focuses on acute care rather than the preventive monitoring highlighted here. The cultural stigma around cognitive decline makes early screening even more crucial. If we push for community‑based blood‑pressure checks and education, we could curb the downstream dementia surge.

Craig E

October 22, 2025 AT 15:10You raise a good point about community outreach; it reminds me of the ancient philosophy that health is a collective responsibility. While individual vigilance is essential, societal structures often dictate the accessibility of follow‑up care. Bridging that gap through local health workers could turn those silent infarcts into detectable markers. Moreover, integrating cognitive tests into routine check‑ups respects the holistic view of well‑being.

Holly Green

October 22, 2025 AT 15:11The checklist is a solid starting point for anyone recovering from a TIA.

Gary Marks

October 22, 2025 AT 15:13Wow, this article really opens the floodgates to a cascade of concerns that most people gloss over when they hear "mini‑stroke." First off, the sheer magnitude of the relative risk numbers-1.68 for all‑cause dementia-makes you sit up straight and take notice, especially when you consider the billions of people globally who flirt with vascular risk factors. The interplay between endothelial damage and amyloid clearance is mind‑boggling, as it suggests that a fleeting ischemic event can set off a chain reaction that accelerates both vascular and Alzheimer’s pathology simultaneously. I love how the piece underscores silent infarcts; they’re the sneaky culprits that accumulate in the hippocampus and frontal lobes like tiny landmines, each whispering a subtle score of memory loss. Then there’s the practical checklist-blood‑pressure targets, antiplatelet therapy, statins, lifestyle tweaks-laying out a clear roadmap that feels both urgent and actionable. Yet, we can’t ignore the socioeconomic reality that many patients won’t have easy access to regular MRIs or even a neurologist, leaving them to navigate this complex maze on their own. The mention of the MMSE and MoCA is helpful, but it also highlights a blind spot: are primary‑care physicians even trained to interpret early cognitive changes after a TIA? Not to mention the cultural variations in how symptoms are reported; in some communities, forgetfulness is dismissed as "just getting old," delaying crucial interventions. The article’s emphasis on aggressive risk‑factor control is spot‑on, but it could have dived deeper into why hypertension remains so pervasive despite clear guidelines. And let’s not forget the hidden player-sleep apnea-which often flies under the radar yet contributes significantly to vascular injury. Finally, the call for annual brain imaging is noble, but the cost implications are massive; perhaps a tiered approach based on initial risk stratification would be more feasible. All in all, this piece stitches together epidemiology, pathophysiology, and practical steps in a way that’s both scientifically robust and clinically relevant, making the invisible threat of post‑TIA dementia impossible to ignore.

Eileen Peck

October 22, 2025 AT 15:15That was a thorough read; the way you broke down each mechanism makes it easier to grasp the stakes. I’d add that regular walks and a Mediterranean diet have been shown to improve endothelial health, which ties nicely into the prevention strategies you listed. Keep spreading the word-awareness is half the battle.

Steven Young

October 22, 2025 AT 15:16Everything sounds neat on paper, but have you ever considered who profits from pushing all these medications and endless scans? The pharma lobby has a vested interest in labeling every TIA as a precursor to dementia; it guarantees a lifetime of prescriptions. And the healthcare industry thrives on chronic disease management, not on curing the root causes. Some argue that the data is cherry‑picked to create a market for new drugs. It’s worth questioning whether the recommended screening schedule is truly patient‑centric or merely a revenue generator for clinics and imaging centers.

Sireesh Kumar

October 22, 2025 AT 15:18Whoa, that’s a hefty accusation, but it does highlight the need for transparency in medical recommendations. I’ve seen patients overwhelmed by the sheer volume of follow‑ups and wonder if they’re being swept up in a profit‑driven cycle.

Jonathan Harmeling

October 22, 2025 AT 15:20While it’s easy to get cynical, the evidence for antiplatelet therapy and blood‑pressure control remains solid, and dismissing it could endanger patients who truly need these interventions. It’s a moral responsibility for clinicians to balance cost concerns with evidence‑based care. Encouraging lifestyle changes alongside medication ensures a holistic approach, not just a profit‑centric one.

Taylor Haven

October 22, 2025 AT 15:21Let’s not forget that many of these “evidence‑based” studies are funded by the same big pharma they claim to critique. The meta‑analysis cited might have hidden biases, and the relative risk numbers could be inflated to sell more drugs. Always read the fine print before accepting recommendations at face value.