Acid Suppression: What It Is, How It Works, and What You Need to Know

When you take a pill to quiet your heartburn, you're using acid suppression, a medical strategy that reduces stomach acid production to relieve symptoms like heartburn and reflux. Also known as gastric acid reduction, it's one of the most common treatments in modern medicine—but it’s not as simple as just taking a pill when it hurts. These drugs don’t cure the problem; they silence the signal. And like any tool used too often, they come with trade-offs.

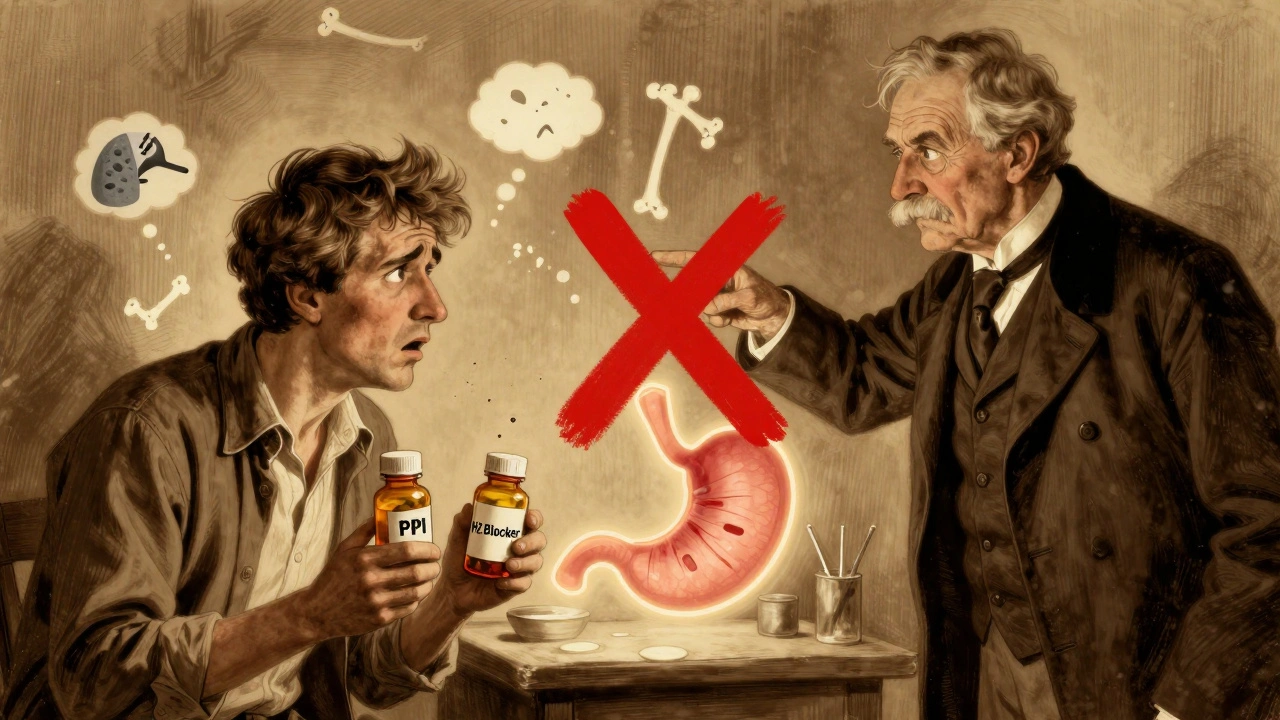

Most acid suppression comes from two main types: proton pump inhibitors, medications like omeprazole and esomeprazole that block the final step of acid production, and H2 blockers, drugs like famotidine that reduce acid by targeting histamine receptors. Both work well short-term. But long-term use? That’s where things get messy. Studies show prolonged acid suppression can lead to nutrient deficiencies—especially in magnesium, calcium, and vitamin B12—because stomach acid is needed to unlock those nutrients from food. It also changes your gut bacteria, which may raise your risk of infections like C. diff. And here’s the twist: many people take these drugs for years, even when their symptoms started from something simple like eating too fast or lying down after meals.

Acid suppression isn’t just about pills. It’s tied to conditions like GERD, hiatal hernias, and even obesity. But not every case needs medication. Some people find relief with posture changes, weight loss, or avoiding trigger foods like coffee, spicy meals, or chocolate. Others need more—like testing for H. pylori infection or checking for esophageal damage. The real question isn’t whether acid suppression works—it’s whether it’s the right tool for your situation, and for how long.

What you’ll find below isn’t a list of drug reviews. It’s a collection of real-world insights from pharmacy practice: how comorbidities make acid suppressants riskier, how drug interactions can turn harmless pills into dangers, and why some people keep taking them long after they should’ve stopped. These posts don’t push a single answer. They give you the facts so you can ask better questions—of your doctor, your pharmacist, and yourself.